Ca Maronn c’accumpagn 2013-2023

Mostra personale, galleria Blocco 13, Roma

15 settembre 15 ottobre

a cura di Adriana Polveroni

«A me bastava che i dadi toccassero terra, anche per pochi secondi. Poi, come quasi in tutti i blitz, sarebbe arrivata la polizia, mi avrebbero fermato. Per giunta eravamo a piazza del Quirinale, a pochi metri dalla presidenza della Repubblica, e quindi lo stop era molto prevedibile».

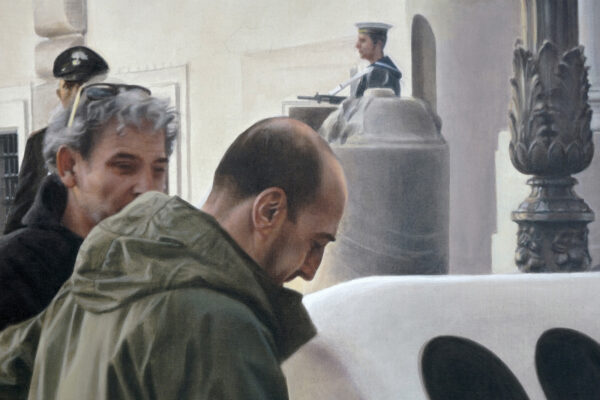

Due grandi dadi toccarono effettivamente terra, rotolarono qualche secondo sotto lo sguardo che Castore e Polluce rivolgono con indifferenza verso il destino di Roma, in quel momento un pessimo destino, non di Roma ma dell’Italia tutta, per via dello stallo politico all’indomani delle elezioni del 2013. Subito dopo arrivò un corpulento carabiniere dall’aspetto bonario che, chissà, quasi quasi si divertiva con quella storia di dadi, di affidarsi alla sorte, alla Madonna, a qualunque cosa pur di uscire da quella patetica impasse dove eravamo finiti. E il blitz di Iginio De Luca ebbe fine. Titolo: ca Maronn c’accumpgn. Anno 2013.

Dieci anni dopo, oggi, 2023, quel blitz prende di nuovo vita, ma in una forma diversa e inconsueta. Diventa un quadro, un grande quadro dipinto con meticolosa attenzione ai dettagli, senza tradirne nessuno. Per cui il carabiniere mantiene la sua aria bonaria mentre intima all’artista di finirla con quell’irriverente auspicio, l’artista continua ad indossare quel curioso grembiule bianco, mentre altri due componenti della squadra rimuovono (in realtà continuando a far rotolare) uno dei due dadi, in lontananza si intravedono altri due carabinieri e, osservando bene la scena, notiamo che le finestre del Quirinale sono chiuse con degli scuri (almeno quelle del primo piano), che il cielo di Roma non splende come a volte riesce a stupire e che, guarda caso, i sanpietrini a terra sono perfettamente allineati, senza neanche uno un po’ storto, sollevato o divelto.

Tutto questo lo apprendiamo dal quadro che ora viene presentato alla galleria Blocco 13 di Roma e che Iginio De Luca ha dipinto, fermando quella scena in un tempo diverso, quale è il tempo lungo, paziente della pittura.

E qui si apre un nuovo capitolo della storia dell’artista, conosciuto per lo più per i suoi blitz, per quelle azioni dal morso situazionista, consumate nell’unità di tempo, luogo e azione, vivificate da quei sottili ma decisivi e spesso irresistibili, slittamenti linguistici, per cui Forza Italia, in una manifestazione di Forzisti, diventa paradossalmente Farsa Italia, con tanto di bandiere mischiate nel corteo, o, più in sordina, la lapide che annuncia Villa Sciarra, si trasforma in Villa Sciatta – memento e metafora di tanti altri insigni, e degradati, luoghi romani – e così via politicamente criticando a suon di ficcanti detournement.

Ma, come lui stesso racconta, Iginio De Luca ha sempre dipinto, pur con «un pudore eccessivo verso la pittura», andando e tornando sulla stessa composizione infinte volte – come si conviene al work in progress, non infiammato dall’istinto gestuale, della pittura – ma non l’ha quasi mai esposta.

«Ho impiegato dieci anni a fare questo quadro, mi piace che sia un ponte tra il blitz del 2013 e il lavoro statico, contemplativo, quasi accademico di oggi. Io nasco figurativo, la mia natura è pittorica e ho un desiderio di pittura molto intenso, perché la pittura ha una profondità enorme mentre la foto è piatta e anche nei miei blitz c’è una figurazione molto forte, un’attenzione ai colori, ma non ho mai mostrato questo lato del mio lavoro. Quindi, in un certo senso questo quadro diventa un blitz con me stesso», racconta De Luca.

Per un artista che ha agito la critica politica con azioni rapide e aggressive, tornare su un’opera del passato con un linguaggio tradizionale, qual è quello della pittura, significa rivedere il proprio lavoro, sfidandolo con una tecnica nuova. Ma, in un certo senso, significa anche rivedere se stessi. Interrogarsi rispetto a quello che si era e confrontarsi con quello che si è oggi.

Sfidarsi quindi, non conoscendone, forse, tutte le conseguenze. Ma senza rinunciare alla cifra più distintiva del suo lavoro. «La critica politica è sempre drammaticamente attuale, nel mio caso fare pittura non denota una scelta estetica, ma diventa un fare politico perché le motivazioni del blitz di allora rimangono attuali. La pittura si contamina, ribadisce che la politica è impotente a gestire i problemi reali delle persone e io denuncio questa realtà con questo quadro. Fermare il tempo, far durare dieci anni quella manciata di secondi, per me significa confermare, in altro modo, la mia posizione di dieci anni fa», afferma De Luca. Che aggiunge: «Ho scelto proprio quel blitz perché non aveva nessun rapporto con la pittura. Presentare oggi solo questo lavoro, con il quale il pubblico dovrà confrontarsi, significa anche riattivare quel blitz. Mi piace pensare che tutto si può trasformare».

Fermiamoci un istante su questa operazione che, a mio parere, non è solo il reenactment di un lavoro precedente, dove la pittura esprime in maniera più poetica la protesta civile di Iginio De Luca. Il quadro che ripropone il blitz ca Maronn c’accumpgn ci mette di fronte a qualcosa che c’è (o che c’è stato, ma il tempo è ininfluente: i dadi che hanno toccato terra per un istante) e a qualcosa che non c’è – il resto del blitz, il prima e il dopo di quel momento specifico, che è semplicemente evocato e che noi, pubblico, siamo chiamati ad immaginare. Anche l’auspicio si colloca su questo crinale: si evoca e s’invoca il futuro, qualcosa che dovrebbe avvenire. Lo sguardo, quindi, è a qualcosa che non c’è.

A ben vedere, tutto il lavoro di Iginio De Luca, pur così apparentemente esplicito, dichiarato, così manifesto anche in virtù della sua valenza politica, si compone sempre di una parte espressa, visibile e di una parte che rimane celata, che è solo evocata. Così è nel suo penultimo lavoro, Tevere Expo, dove De Luca ha fotografato gli oggetti che il Tevere lascia riaffiorare, facendoci immaginare un mondo che rimane nascosto, ma che esiste nella profondità melmosa del fiume. Così è stato per i “gommoni” che Silvio ci ha rotto, per la proiezione Lavami sulla cupola di San Pietro, di cui riconosciamo la grafia delle scritte Lavami (che non vediamo) sulle macchine impolverate.

Alcune volte la parte mancante è addirittura la più importante. Quando De Luca afferma che gli “bastava che i dadi toccassero terra”, ci suggerisce che tutta l’azione, l’intero blitz con il quale l’artista si sarebbe appropriato, anche per un solo istante, di un luogo altamente istituzionale e sorvegliatissimo (vero reenactment situazionista!) era la parte più importante del lavoro, che non avremmo mai visto, ma che possiamo immaginare.

Da questo punto di vista, direi che il lavoro di Iginio De Luca sia da sempre molto poetico, in quanto invito all’immaginazione, a completare la sua opera, ad accompagnare il gesto dell’artista.

Facendo diventare anche noi, non solo complici, ma un po’ situazionisti. Almeno con la fantasia.

Adriana Polveroni

Ca Maronn c’accumpagn 2013-2023

Personal Exhibition, gallery Blocco 13, Rome

15 september 15 october

Curated by Adriana Polveroni

For me, it was enough for the dice to touch the ground, even for a few seconds. Then, as in almost all blitzes, the police would come and stop me. What’s more, here we were in Piazza del Quirinale, a few steps from the President of the Republic, and therefore the stop was very predictable”. Two large dice actually landed, they rolled for a few seconds under the gaze that Castor and Pollux turn with indifference towards the fate of Rome (at that moment a bad one, not just for Rome but of all of Italy, due to the political stalemate following the 2013 elections). Immediately afterwards a burly but good-natured carabiniere arrived who — who knows? —was almost enjoying the story of the dice, to rely on fate, on the Madonna, on anything to get out of that pathetic impasse where we had ended up. And Iginio De Luca’s blitz came to an end. Title: Ca Maronn c’accumpagn. Year 2013.

Ten years later, today, in 2023, that blitz comes to life again, but in a different and unusual form: as a large painting executed with meticulous attention to detail, misrepresenting no one. The carabiniere maintains his good-natured air while ordering the artist to cease, to stop expressing that irreverent hope. The artist persists, wearing a curious white apron as two other members of the team remove (actually continue to roll) one of the two dice. In the distance, two other carabinieri observe the scene. We notice that the shutters of the Quirinale are closed, at least those on the first floor, and that the sky of Rome does not shine amazingly as it sometimes does, and that the cobblestones (sanpietrini) are perfectly aligned, not one even a little crooked, raised or uprooted.

We learn all this from Iginio De Luca’s painting that is now exhibited at the Blocco 13 gallery in Rome, which arrests the scene at a different time, that long, patient time that belongs to painting.

And here a new chapter opens in the history of the artist, best known for his “blitzes”, actions with a Situationist bite, realized in a unity of time, place and action, enlivened by subtle and decisive linguistic shifts. Forza Italia, in a demonstration by its supporters, paradoxically becomes Farsa Italia, complete with flags mixed up in the procession, or, more gently, the plaque announcing Villa Sciarra, turns into Villa Sciatta, reminder and metaphor of many other famous, degraded Roman places, and so on: ordinary images used in a subversive political critique.

As he says himself, Iginio De Luca has always painted, albeit with “an excessive modesty towards painting”, returning over and over to the same composition, as befits a work in progress, treating it coolly, without inflamed gesture, and rarely exhibiting it.

“It took me ten years to complete this painting, I like that it is a bridge between the blitz of 2013 and today’s static, contemplative, almost academic work. I was born figurative, my nature is pictorial. I have a very intense desire for painting, because painting has an enormous depth, while a photo is flat. Even in my blitzes there is a very strong figuration, an attention to colours. But I have never shown this side of my work. So, in a certain sense this painting becomes a blitz with myself”, says De Luca.

For an artist who has expressed political positions with rapid and aggressive actions, returning to a work from the past while using the traditional language of painting means re-assessing his own work, challenging it with a new technique. In a certain sense, it also means seeing himself again, confronting who he was with who he is today, challenging himself—perhaps ignoring the consequences, but not renouncing the most distinctive aspects of his work.

“Political criticism is always dramatically current. In my case painting does not denote an aesthetic choice, but becomes political because the reasons for the blitz of the time remain current. Painting is contaminated, it asserts that politics is powerless to manage people’s real problems, and I underline this reality with this painting. Stopping time, making that handful of seconds last ten years, for me means confirming, in another way, my position of ten years ago,” says De Luca, who adds: “I chose that blitz precisely because it had no relationship with painting. Presenting only today this work, for the public to contemplate, also means reactivating that blitz. I like to think that everything can be transformed”.

For a moment let’s pause this operation, which in my opinion is not simply the translation of a civil protest into the more poetic genre of painting. The painting that revisits the blitz ca Maronn c’accumpagn presents us with something that is (or—time being irrelevant—that was, that has actually happened, as the dice have touched the ground for an instant) along with something that is not (the rest of the blitz). Of that specific moment there is a before and an after: a consequence that is evoked, that we viewers are called upon to imagine. Even the work’s implicit hope is placed on this divide, as the future is evoked and invoked; it is something that still must happen. Our gaze, therefore, is directed at something that is not there.

On closer inspection, all of Iginio De Luca’s work, even that with apparently explicit political content, is made up of an expressed, visible part and another part that remains concealed or barely suggested. This also characterizes his penultimate work, Tevere Expo, in which De Luca photographed the objects that resurfaced from the Tiber, inviting us to imagine a world that remains hidden, but which exists in the muddy depths of the river. This was the case with the inflatable boats that Berlusconi wrecked for us, for the Lavami (wash me) projected on the dome of St. Peter’s, which recalls the familiar phrase written on dusty cars.

Sometimes the missing part is even the most important. When De Luca states that, “it was enough for the dice to touch the ground”, he is suggesting that the entire blitz and all of its action, with all its institutional and Situational weight—from which he has appropriated a only single instant—is the work’s most important aspect, even if only imagined and never seen.

The work of Iginio De Luca has always been highly poetic, an invitation to the viewer to accompany the artist’s gesture and to complete the work, making us not only accomplices, but also a bit Situationists, at least in our imaginations.